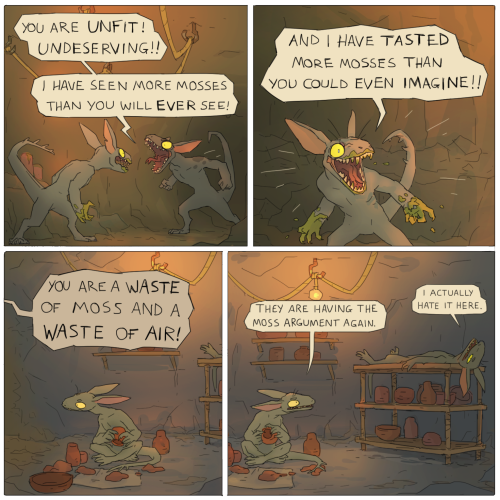

Lost In The Moss

lost in the moss

More Posts from Souppooppie and Others

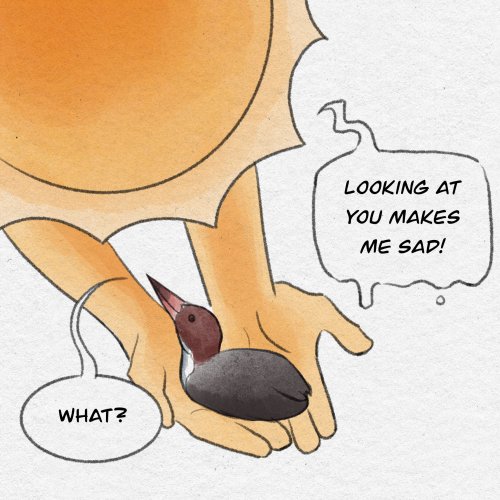

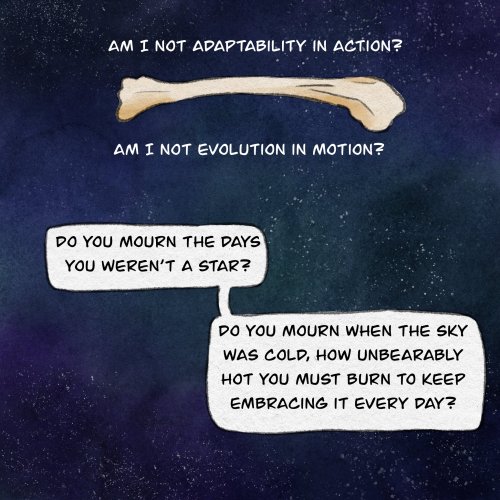

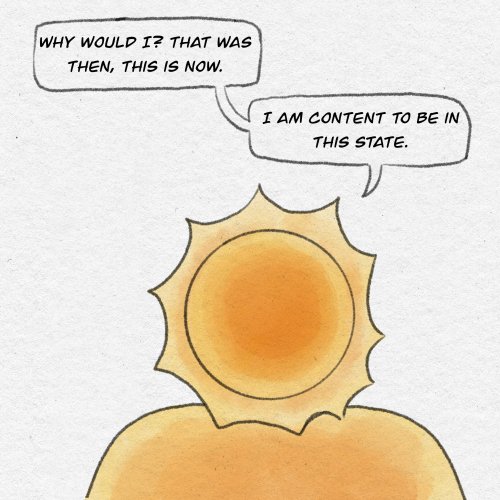

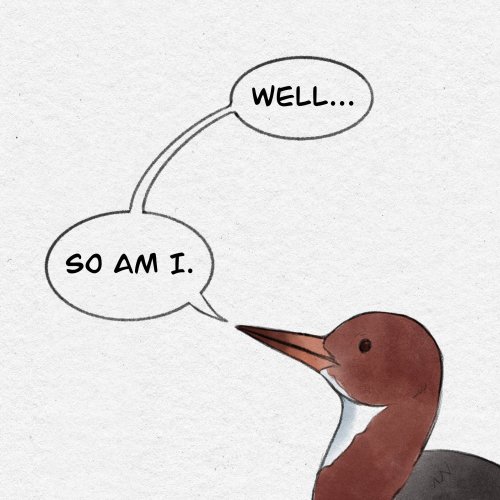

the sun mourns in vain for the white-throated rail: a comic about disability and the unwanted able-bodied grief for past selves.

[IMAGE DESCRIPTION:

Page 1: The sun holds a white-throated rail, a bird with a red head, a gray body, and a white throat, in its hands. The sun speaks in a tone represented as sorrowful pity through a drippy speech bubble.

Sun: Looking at you makes me sad!

Rail: What?

Page 2:

Sun: Looking at you makes me sad!

The sun stands with a hand clutching its face.

Sun: How miserable it must be to be flightless! Don’t you yearn for the skies? Don’t you wake up grieving you’re still on land?

Page 3: The white-throated rail looks down in frustration in the hand of the sun.

Sun: (speaking off screen) I’d simply perish if I were you!

The rail speaks, looking down. Pink flowers bloom towards the bottom of the page, petals and pollen blowing in the wind.

Rail: Why do you put your words in my beak and your grief in my feathers? Am I not beautiful?

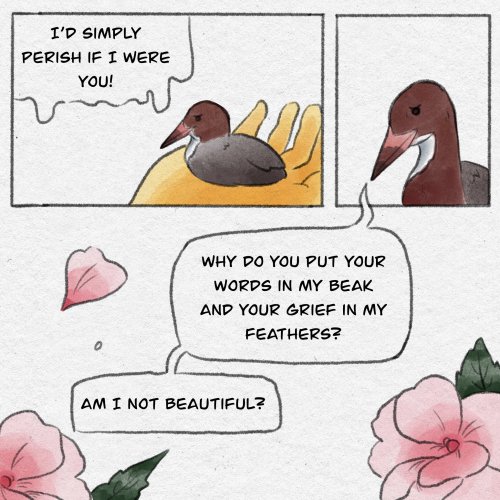

Page 4: The bone of a white-throated rail is positioned against a colorful galaxy dotted with flecks of stars.

Rail: Am I not adaptability in action? Am I not evolution in motion? Do you mourn the days you weren’t a star? Do you mourn when the sky was cold, how unbearably hot you must burn to keep embracing it every day?

Page 5: The sun looks at the viewer.

Sun: Why would I? That was then, this is now. I am content to be in this state.

Page 6: The rail looks up at the sun off-screen.

Rail: Well…So am I.

have me as a guest on your podcast. im not an expert in anything. i dont work in an interesting industry. i have very few skills. i don’t have anything i want to talk about. my voice is weak and i can’t project it well. im not funny. im the perfect guest for your podcast.

" yoUr exCuse is That YoU foRgOT- EVERYTTIME- YOU ALWAYS SAID THAT yOU ForgOt "

LIKE BITCH YOU THINK I CONTROL IT?!-

DUMB BITCH

Dragon Knight by Jian Li

@we-are-knight

Howl, throwing his head on Sophie's lap and looks up at her innocently: Sophie, tell me I'm pretty.

Sophie, resting her hand on Howl's cheek and smiles lovingly at him: You're pretty fucking annoying that's what you are.

Short Story Plot: How to Use Ideas and Structure to Plot a Short Story

Do you want to write a short story, but are unsure about how to develop a short story plot?

Short stories rarely require extensive plotting. They’re short, after all. But a bit of an outline, just to get the basic idea down, can help you craft a strong plot.

Plotting your short stories will give you an end story goal and will help you avoid getting stuck in the middle, or accidentally creating plot holes. You’ll have fewer unfinished stories if you learn to do a little planning before you start writing.

And in this article, you can learn how to take your short story’s primary conflict, and build a plot around it.

Definition of Plot and Structure

I see the terms “plot” and “structure” thrown around interchangeably quite a bit, so I’d like to correct that before we move on.

Plot is a series of events that make up your story.

Structure is the overall layout of your story.

Plot is (most likely) unique to your story, but there are a handful of basic structures that are universal and used over and over again. (We’ll get into the basic three act structure in a later post.) Structure is the bones and plot is what fills it out.

You can learn more about plot and structure in this article, or the different story types here.

The Strength of a Short Story Idea

When I first started out writing short stories, I had no idea where I was going with any of them. Absolutely none. I see this time and time again with newer writers. I think it’s because we’re conditioned to think any kind of art is only driven by that infamous and often elusive muse rather than hard work. I felt the same way.

And then I started getting more stories under my belt. Some I finished. Some I didn’t.

You know what the difference was? The stories I finished, I plotted before I wrote.

Now I know a lot of writers loathe plotting or outlining stories—of any length, but especially short stories. They have various reasons for this dislike, but the most common one I hear is planning or outlining takes all the “magic” out of writing. “Creative writing is about being creative!”

I won’t get into the idea that writing is actually a job here—it is. That’s not what this article is about.

Instead, I’m going to propose a different reason for planning a short story with one important question: Is your idea even a story?

Planning out your story, even if it’s short, can give you an answer to this question. It will determine whether or not your central character can work towards achieving a goal (and simultaneously the plot moves towards a climax), or if your idea ends there—at the idea.

Writer’s tip: If you’re feeling stuck on coming up with an idea that could withstand a story’s length, try looking at the types of plots discussed in this article.

Is It a Story or Just a Story Idea?

Don’t panic. I don’t plan extensively. But what I’ve found was absolutely no planning whatsoever more often than not leads to wasted time. Nobody has time to waste.

If I don’t plot at all, I’ll get maybe a third of the way through the story and get stuck. I’ll have no idea where it was going, and without that goal in mind, I’ll flounder. I might tinker around with the idea a little longer, but most of the time I’ll end up abandoning the story.

A few weeks ago, I had the infamous muse visit me. I grabbed my notebook and started writing. It was great writing. The prose was good, the main character was crazy interesting, ditto for the secondary character, and I’d set up a mystery that made you want to turn the page. The problem was I had no idea what the mystery was. I had set up and no payoff. This story idea fizzled out at the start of the second act.

Now, to be clear, I do indulge my muse every once in a while. It does feel good to be taken over by an idea, even if you don’t know where it’s going. It’s all very “artisty.”

But the fact is I’ve sold one story that I finished without plotting it beforehand. One. Out of dozens I’ve started. That one took me about a week to write and it was torture for me, for my characters, and, I’m sure, for the backspace on my keyboard. Everything about the story reads as forced. It’s uninspired. And you know what?

That’s the one my muse started me on! Inspiration is supposed to be the point of the muse, right? But a muse can only get you started; it can’t keep you going.

Your muse won’t finish a story for you.

When your muse starts poking at you and you don’t know if your idea is a story, ask yourself a couple of questions:

Am I going to remember this idea tomorrow? Yes, it’s nice to be taken over by inspiration. Feel free to indulge that every so often. But also be prepared to have an unfinished story on your hands. You don’t necessarily have to wait until tomorrow to write the thing (especially when we’re talking about shorts), but you do need to know if your enthusiasm is going to wan a few minutes down the road when your muse decides to go take a nap, leaving you with nothing but frustration. (That story I mentioned a moment ago? I haven’t completely forgotten about it, but it does not sit at the top of my mind.)

Do I have a “What if?” question and an answer to that question? If you’re thinking about beautiful sentences where nothing is happening, that’s probably not a story. If you can’t think of an end goal for your character, that’s probably not a story. See the next section for more on “What if?” and the answer. (The story I didn’t finish did not have a goal in mind.)

Do you have a character? This one seems like a no-brainer, but you’d be surprised how often I used to start “stories” and just ramble on with purple prose. No people, no action, no story.

If the answer to all these questions is “yes,” then you most likely have a finishable story. If it’s “no” tell your muse to go back to its hole until it can come up with something better.

If you must, explore the idea a little more and see if you can’t plot a little something. (Do not write yet!)

Enter the “What if?” question.

What If? How Asking This Question Can Plot a Short Story

In the last post, I told you my favorite way to think of a short story idea is the “What If?” question. This question can help you think about various ways to put your central character into a conflict, like: What if X happened? It’s your own mind giving itself creative writing prompts.

Let’s expand on that method a bit. Notice it’s a question. And questions often have answers, do they not? Knowing the answer to your “What If?” question is the most basic outline of a story.

Let’s start with a basic question.

Q: What if someone knocked on my door?

A: I’d probably ignore it.

That’s it. That’s the story. It’s kind of crappy, right?

Notice that answer is my immediate reaction to the knock. It’s not something that happens down the road. That’s part of what makes this scenario NOT a story.

The other issue here is there is no conflict. I don’t answer the door, the person goes away, and I’m left to my own devices. There are no consequences for my decisions, so nothing happens—and nobody reading about this incident cares.

Without conflict, there are no stakes in a story. No conflict equals no story.

What Makes a Good Conflict?

Remember conflict can come in many forms and doesn’t have to be a shoot ’em up kind of situation. Internal conflict can also make a short story. But there MUST be conflict.

So, on multiple levels, this question and answer session is a loser.

Now, let’s say I don’t answer the door. (I’m a millennial. I’d rather not talk to people if I can help it, so this really is the most likely thing to happen.) The person assumes I’m not home. But wait! They’re a burglar. They now try to break into my house. The “What If?’ question has now changed to “What if someone tried to break into my house while I was home?”

See how the central character has to do something now? Even if they don’t, there will be consequences.

Because the story idea establishes stakes, I know I’ve got something. How do I know? There are myriad possibilities here. I could call the cops. I could run out and confront them myself. I could freeze and run upstairs and hide. I could sic my dog on them. I could wait for them to get inside and invite them to join me in having a cup of tea.

Whatever I choose to do, there will be a cause and effect trajectory of events. Which means more stakes, and more opportunities that force my protagonist to face their conflict. They have to make decisions, which will lead to a whole slew of other “What If?” questions:

What if they get in before the cops get here?

What if they break a window?

What if my dog was outside and they hurt him?

What if a neighbor sees them and comes running over?

What if they “break in” but it’s really just my sister needing in my house for something?

What if I’m hiding under the bed and they find me?

What if they hate tea?

What if … and the list goes on.

These are all more interesting scenarios than just ignoring the door and the person going away. But we’re still looking for the answer to the initial “What If?” question. The answer solves the question and puts it to bed. It doesn’t lead to other questions.

Don’t Forget to Answer Your What If Questions

A short story only has one to three scenes normally, so your answer needs to come in a short span of time. It can’t come years down the road. Any span of time longer than a few hours, maybe a day or two, is probably too long.

Q: What if someone tried to break into my house while I was home?

A: I would call the cops, but also grab my bat and be ready to use it.

But wait. That still doesn’t answer the question, not in a final way. There’s still an open ending there, still questions. (Did I use the bat? What happened if I did?) Let’s try again.

A: I would decide not to use my bat and would talk to them until the police got there.

That’s better. With this scenario, I can think of a couple of things that would happen after the police got there, but at that point the situation is over. I’ve done it. I’ve defeated the burglar. Anything afterwards is a conclusion to the story.

The best part is, I’ve actually done it in a way that means change for me as a central character. I didn’t want to talk to anyone to begin with, which is what led to the whole situation. But I have to overcome that aversion by talking to someone in order to solve the problem.

Short Story Structure

We’ve got two important elements of the story narrowed down now: the “What If?” question and its ultimate answer.

If you’ve been following this blog for a while, you might have come across the many posts we have about plot structure. In a story you need six things:

Exposition (Background and setup.)

Inciting Incident (A major event happens to your character.)

Rising Action (or progressive complications, a sequence of events where things get worse.)

Crisis (Ah, what is your character going to do?)

Climax (Showdown based on what your character decided to do.)

Denouement (Finish it up.)

Need a refresher on these plot elements? Dive further into story structure here.

A short story is often only one to three scenes. That means this structure, these six elements, stretch over the entire story to form the framework. (The scenario I’ve presented would most likely be a one-scene story.) Notice I’m talking about framework here. These six elements are your story structure.

So what do we have here after all this thinking about questions and answers?

The “What If?” question is your Inciting Incident.

The ultimate answer is your Climax.

Boom. Two elements down. And these two elements happen to be the bulk of what your readers will remember from your story.

We’ve planned a story, believe it or not. And it didn’t even hurt that much.

But wait! There’s more. (Sorry, couldn’t help myself.)

In the process of coming up with these two elements, we’ve inadvertently come up with a couple of others.

Choosing not to use the bat and talking to the burglar instead? That’s the Crisis. All those streams of “What if?” questions? Those are progressive complications.

Whoops. We’ve outlined basically the whole thing, haven’t we? I sort of tricked you there. Sorry, not sorry.

Plotting Doesn’t Hurt—Too Much

Plotting a short story doesn’t have to be a meticulous thing that requires hours of work and a running spreadsheet. It also doesn’t have to take the magic out of writing.

Your plan for your short story can be a simple, loose outline. (By the way, outlines can change if you think of something better! They’re not set in stone.) Really, you just need two elements to get to writing a short story:

A “What If?” question (identifies the Inciting Incident)

The answer (shows the Climax)

And then you’re ready to write!

In future articles, we’ll dive more into writing structure and the essentials and plot elements of a short story. For now, use this “shortcut” to plan out a few short stories of your own! Have fun with it!

Source

I love you tragedy I love you corruption arcs I love you doomed relationships I love you character succumbing to their fatal flaw I love you codependency I love you characters doomed to die from the start I love you road to hell paved with good intentions

anime_irl

Some individuals with AD/HD, especially without hyperactivity, have an activation problem as described by Thomas Brown, Ph.D. in his article AD/HD without Hyperactivity (1993). Rather than a deficit of attention, this means that individuals can’t deploy attention, direct it, or put it in the right place at the right time. He explains that adults who do not have hyperactivity often have severe difficulty activating enough to start a task and sustaining the energy to complete it. This is especially true for low-interest activities. Often it means that they can’t think of what to do so they might not be able to act at all, or, as Kate Kelly and Peggy Ramundo say in You Mean I’m Not Lazy, Stupid or Crazy?!, they might experience a “paralysis of will” (pg. 65). “The clothes from my trip—a month ago—are just still lying in a heap in the suitcase.” “I spend a lot of time in bed watching TV but my mind isn’t watching TV. I’m thinking about what I should be doing, but I don’t have the energy to do it.”

- Sari Solden, Women With Attention-Deficit Disorder

I'd try this out tbh if it were not for the emotional side of executive functioning that made it like there's no point to this. the brain going crazy just visualizing getting the thing out / writing things down because first, that feels like a lot of emotional energy is required. Second, doing the actual task? that feels like a lot of emotional energy is required. like fuc- whEN WILL THIS CYCLE END

Recently accidentally discovered the best executive dysfunction hack I’ve ever found

Ok so we’ve all heard of tips involving lists, make a list of everything you need to do, cross it out when you’re done, etc.

Well recently next to each item on my list, I wrote down how to start that task. This can be as simple as “get out my notebook and the assignment” or a little more detailed like “open chemistry textbook to page 235 and review the section on gibbs free energy”

Basically, you do all the executive functioning all at once before you start your tasks! Now when you get to the task, your brain doesn’t need to access that executive functioning to figure out how to start, you’ve already done it. Even stupid stuff like “take the assignment out of your backpack” helps a weird amount when it’s written down. Like it helps more than you think it should. I was rolling my eyes up until the point where it worked

-

electronicosmos15 liked this · 1 week ago

electronicosmos15 liked this · 1 week ago -

vampireknitting reblogged this · 1 week ago

vampireknitting reblogged this · 1 week ago -

vampireknitting liked this · 1 week ago

vampireknitting liked this · 1 week ago -

luna-drinker reblogged this · 1 week ago

luna-drinker reblogged this · 1 week ago -

benevolent-mushroom reblogged this · 1 week ago

benevolent-mushroom reblogged this · 1 week ago -

sadgothtransbian reblogged this · 1 week ago

sadgothtransbian reblogged this · 1 week ago -

sadgothtransbian liked this · 1 week ago

sadgothtransbian liked this · 1 week ago -

frithuritaks liked this · 1 week ago

frithuritaks liked this · 1 week ago -

mothyeatensweater reblogged this · 1 week ago

mothyeatensweater reblogged this · 1 week ago -

path-of-the-sound reblogged this · 1 week ago

path-of-the-sound reblogged this · 1 week ago -

elegantbarbarianstudent reblogged this · 1 week ago

elegantbarbarianstudent reblogged this · 1 week ago -

cloud-for-one liked this · 1 week ago

cloud-for-one liked this · 1 week ago -

indeterminategroundmeat liked this · 1 week ago

indeterminategroundmeat liked this · 1 week ago -

indeterminategroundmeat reblogged this · 1 week ago

indeterminategroundmeat reblogged this · 1 week ago -

scbhtvbtggt liked this · 1 week ago

scbhtvbtggt liked this · 1 week ago -

crocodileslastcigar reblogged this · 1 week ago

crocodileslastcigar reblogged this · 1 week ago -

crocodileslastcigar liked this · 1 week ago

crocodileslastcigar liked this · 1 week ago -

mcfries123 reblogged this · 1 week ago

mcfries123 reblogged this · 1 week ago -

kappykrow reblogged this · 1 week ago

kappykrow reblogged this · 1 week ago -

kappykrow liked this · 1 week ago

kappykrow liked this · 1 week ago -

gruntildaboy liked this · 1 week ago

gruntildaboy liked this · 1 week ago -

dreadbirate reblogged this · 1 week ago

dreadbirate reblogged this · 1 week ago -

veggiepizza-noolives liked this · 1 week ago

veggiepizza-noolives liked this · 1 week ago -

lmaxell reblogged this · 1 week ago

lmaxell reblogged this · 1 week ago -

attentiondeficitastartes reblogged this · 1 week ago

attentiondeficitastartes reblogged this · 1 week ago -

attentiondeficitastartes liked this · 1 week ago

attentiondeficitastartes liked this · 1 week ago -

onetimemacareblogs reblogged this · 1 week ago

onetimemacareblogs reblogged this · 1 week ago -

creeperstorm103 liked this · 1 week ago

creeperstorm103 liked this · 1 week ago -

mordy-is-gay liked this · 1 week ago

mordy-is-gay liked this · 1 week ago -

s-h-a-s-e reblogged this · 1 week ago

s-h-a-s-e reblogged this · 1 week ago -

s-h-a-s-e liked this · 1 week ago

s-h-a-s-e liked this · 1 week ago -

robocookies liked this · 1 week ago

robocookies liked this · 1 week ago -

lowlife-in-high-orbit liked this · 1 week ago

lowlife-in-high-orbit liked this · 1 week ago -

iztdm liked this · 1 week ago

iztdm liked this · 1 week ago -

1247 liked this · 1 week ago

1247 liked this · 1 week ago -

peruvianprick reblogged this · 1 week ago

peruvianprick reblogged this · 1 week ago -

peruvianprick liked this · 1 week ago

peruvianprick liked this · 1 week ago -

obsidian-flame reblogged this · 1 week ago

obsidian-flame reblogged this · 1 week ago -

thegingerfaggot reblogged this · 1 week ago

thegingerfaggot reblogged this · 1 week ago -

fiachdubh reblogged this · 1 week ago

fiachdubh reblogged this · 1 week ago -

puertovegan reblogged this · 1 week ago

puertovegan reblogged this · 1 week ago -

marsfriend liked this · 1 week ago

marsfriend liked this · 1 week ago -

clangpan reblogged this · 1 week ago

clangpan reblogged this · 1 week ago -

whiskeythefishski reblogged this · 1 week ago

whiskeythefishski reblogged this · 1 week ago -

whiskeythefishski liked this · 1 week ago

whiskeythefishski liked this · 1 week ago -

nerd-guy-bry reblogged this · 1 week ago

nerd-guy-bry reblogged this · 1 week ago -

irremax liked this · 1 week ago

irremax liked this · 1 week ago -

nerdilings liked this · 1 week ago

nerdilings liked this · 1 week ago -

miraviglioso reblogged this · 1 week ago

miraviglioso reblogged this · 1 week ago